In 1780, the area now known as Fort Payne, was named after the Cherokee Chief “Red-Haired” Will Weber. The name of this locale was known as Willisi and then Will’s Town. What is officially now called DeKalb County was known as Will’s County until 1836 when the name officially became DeKalb County. The first general use of the name “Fort Payne” came several years after the Cherokee removal stockades had been abandoned in 1838. Fort Payne became an official name in 1869 and on May 5th, 1878, Fort Payne became the county seat of DeKalb County.

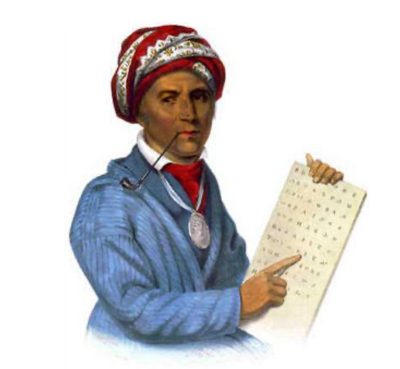

In the 1820’s Will’s Town was home to a remarkable man by the name of Sequoyah. Sequoyah was a Cherokee Chief who single-handily created an alphabet that allowed an entire nation of Indians the ability to read and write.

In 1838 Fort Payne was the site of the Trail of Tears. This was the forced evacuation of the Cherokee Indians to Oklahoma. Failure of the federal government to provide ample means of transport for personal belongings, the Cherokees were forced to leave behind many of their prized possessions, further stripping them of their pride and human dignity. Their journey west was filled with hardships, suffering and illnesses and one out of every seven died before reaching the land they would then call home.

In 1885, coal and iron ore were discovered in the area and investors envisioned a Pittsburgh of the South. The Fort Payne Coal and Iron Company was organized in 1888 and purchased 32,000 acres in and around Fort Payne. The City of Fort Payne was incorporated on February 28, 1889.

The Boom Years began. The influx of “Yankee” investors swelled the population from about 450 to thousands. A 125-room hotel was built and occupied an entire city block. The Fort Payne Depot was built in 1891 and the Fort Payne Opera House in 1889 to help accommodate the growing population. Businesses were established and many lovely homes constructed.

In the 1890s, iron and coal deposits began to play out and coupled with a national economic panic the Boom ended in 1893.

In 1907, a new era began… the era of the hosiery mill. Fort Payne would soon become the largest single location of hosiery manufacturing in America and become known as the “Sock Capital of the World”.

Today steel-fabricating plants, home-fabricating plants and many other diversified industries add to the financial well being of the town. A new and lucrative tourist industry is also being developed in Fort Payne, where the many natural scenic wonders of the area are a great attraction, as well as the historical sites of the boom era.

Sequoyah and the Trail of Tears

Sequoyah, the Cherokee Indian who is celebrated as an illiterate genius who endowed a whole tribe with learning, was born to a Cherokee mother and a German father. When Cherokee Chief Sequoyah moved to Will’s Town, Alabama from the Overhill town of Tuskegee in Tennessee, he enlisted in the Cherokee Regiment, fighting beside Sam Houston and Andrew Jackson in the Battle of Horseshoe Bend in the War of 1812, which effectively ended the war against the Creek Indians. During the war, he became convinced of the necessity of literacy for his people. He and other Cherokees were unable to write letters home, read military orders, or record events as they occurred.

In the early 1820s, Sequoyah developed the Cherokee alphabet. Sequoyah is the only man in history to conceive and perfect in its entirety an alphabet or syllabary. It was while living in Will’s Town that he finished the alphabet that took him 12 years. Within a few months almost all of the Cherokee Nation could read and write.

Captain John G. Payne arrived in Fort Payne, then known as Will’s Town, in February 1838 and approved a site for an Indian stockade near Big Spring. In March, Captain James H. Rogers, commanding 20 men and two officers, garrisoned at Big Spring and built the stockade which he named Fort Payne in honor of his friend, Captain Payne.

In 1838, the Cherokee Indians, native to the area, were rounded up, placed in stockades and then marched to Oklahoma. The march, of course, is well known as the “Trail of Tears”. The mission workers who had established a mission at Will’s Town in the 1820’s protested; however, the forced removal of the Native Americans continued. In 1838 Sequoyah walked with his people in the Trail of Tears.

Today there is no fort or stockade, just an old chimney standing as a stark reminder of what the Cherokees and other Indian tribes endured. Historic markers now stand where Indians once gathered to learn to read and write using an alphabet created and taught by Indian Chief Sequoyah and one where a fort once stood and held Indians against their will.

While we can’t turn back the clock and undo this tragic act, we can at least bring awareness to it and educate others in the hope that this never happens again to another race of people.

The DeKalb County Tourist Association has worked closely with the Alabama-Tennessee Trail of Tears Corridor Association to see this Trail of Tears route marked as a constant reminder of this great Cherokee Nation. Installment of the Trail of Tears “Trail Blazer” markers began December 18, 2000 in Fort Payne for the John Benge Route. The route is being marked from the Fort Payne Improvement Authority to the visitor center in Guntersville. We hope other communities will continue this project to see the trail “Blazed” from Fort Payne to its end in Tahlequah, Oklahoma.

The Boom Years

The Boom Years

The Wills Valley Railroad was incorporated in 1852, and the decades of 1860 and 1870 witnessed the coming of the railroad which gave Fort Payne and the county rail connections with the leading cities of the country. This was a crucial innovation for the city that offered great opportunity for growth.

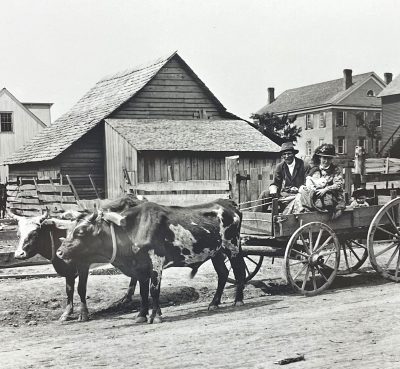

Fort Payne, in 1887, was a small rural community, a little village of less than 500 people, surrounded by Wills Valley cotton fields. The families making their livelihood here included those of the McCartneys, Claytons, Greens, Duncans, Poes, Cravens, Garretts, Lyons and Smiths. Weather and crops were important topics of conversation, though some attention was given to news of the industrial growth in the Birmingham-Bessemer area of the Alabama mineral belt. But that was almost 100 miles away.

Rumors did persist that Fort Payne, too, was surrounded by rich mineral deposits. But none of the original residents here could have predicted the mad rush of prospecting, speculation and development which was soon to descend upon them. For, of all the industrial booms which developed in north Alabama towns thought to be possibilities for future “Magic Cities”, Fort Payne’s boom was by far the most colorful and spectacular.

The three-year boom period, which began in 1889, was to provide historians and amateur buffs with more absorbing factual material – as well as exaggerated myths – than had the whole previous fifty-year period beginning with the forced removal of the Indians.

Fort Payne, with its small school, one church building and few businesses, had not grown much in its half century of existence and remained an unincorporated village when wealthy and ambitious men focused their attention upon some mineral samples from a ridge and devised fantastic plans for a giant manufacturing city.

Fort Payne, with its small school, one church building and few businesses, had not grown much in its half century of existence and remained an unincorporated village when wealthy and ambitious men focused their attention upon some mineral samples from a ridge and devised fantastic plans for a giant manufacturing city.

Four men, Milford W. Howard, C. O. Godfrey, W. P. Rice and J. W. Spaulding, were responsible for the speculation mania which was touched off in Fort Payne in l889.

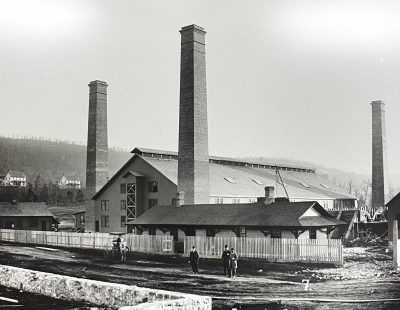

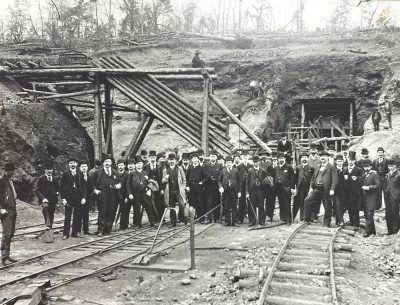

In 1885, coal and iron ore were discovered in the area and investors envisioned a Pittsburgh of the South. The Fort Payne Coal and Iron Company was organized in 1888 and purchased 32,000 acres in and around Fort Payne. The City of Fort Payne was incorporated on February 28, 1889.

The Fort Payne Coal and Iron Company, having by now purchased 32,000 acres of land in the vicinity, immediately set about designing a city and preparing for hordes of speculators and fortune seekers. Streets were graded and new ones opened across the valley and up the ridges. A water supply was developed and a two-mile-long sewage system was constructed at a cost of $35,000.

The Boom Years began. The influx of “Yankee” investors swelled the population from about 450 to thousands. Mines were being opened and more and more laborers and investors arrived at Fort Payne. Industrial companies, banks and investment companies were organized, and stores, schools and churches were built. The DeKalb Hotel, occupying an entire square in the center of town, was constructed. The largest and best equipped hotel in northeast Alabama, this hotel boasted 180 rooms, a billiard room, a huge dining room and a ballroom. The owners refused offers as high as $100,000 for this hotel. Nearby an $80,000 opera house, now a tourist attraction, was built.

To landscape the city, the Fort Payne Coal and Iron Company hired Charles Landstreet who had come here from Virginia in 1887. Public parks were created, including Union Park across from the DeKalb Hotel, the site of the present City Park on Gault Avenue. One of the most interesting attractions developed under Landstreet’s supervision was Manitou Cave, located in the side of Lookout Mountain. Bridges and winding stairways were built leading to the huge ballroom, where dancers could watch the reflections of hundreds of candles glitter from the stalactites of the walls and ceiling. Later electricity was installed inside the cave and a public park created near the entrance.

To facilitate the movement of ores and fuel, the Fort Payne Coal and Iron Company even built and equipped a railroad. The Mineral Railroad, begun in 1889 and completed the following January, ran from the Alabama Great Southern Railroad in the valley in a northeastern direction to Beeson Gap and eastward to its terminal at the Lookout Mountain Coal Mine. A network of sidings in the manufacturing district made it possible to load and unload freight at the factories. The train consisted of’ a locomotive, combination passenger and baggage coaches and coal and construction cars. Regular routes were run from the city to Lookout Village. A considerable amount of passenger and freight service was provided for the public in addition to the company’s business.

By 1890 Fort Payne had quite an impressive directory of businesses and factories. The Fort Payne and the Bay State Furnaces had been constructed. The Fort Payne Rolling Mill and Steel Company was said to be the largest of its kind in the South. The Alabama Builders’ Hardware Company was one of the most extensive hardware manufacturing factories in the South, and a stove foundry was being constructed by the Fort Payne Stove Works. The Fort Payne Basket and Package Factory, located two miles south of Fort Payne, and the Fort Payne Fire Clay Works appeared to be promising industries.

During the latter half of 1890, it began to appear that the mineral resources, especially coal and iron, were below expectations both in quality and quantity. Thus far the Fort Payne Coal and Iron Company had actually been operating at a loss. This, coupled with a national economic panic, ended the Boom in 1893.

The Hosiery Era

Fort Payne’s population at the beginning of the new century was approximately 1700, as compared with over 3500 in 1890. Most of its citizens realized that the city’s future prosperity would depend upon small industries and the surrounding agricultural area.

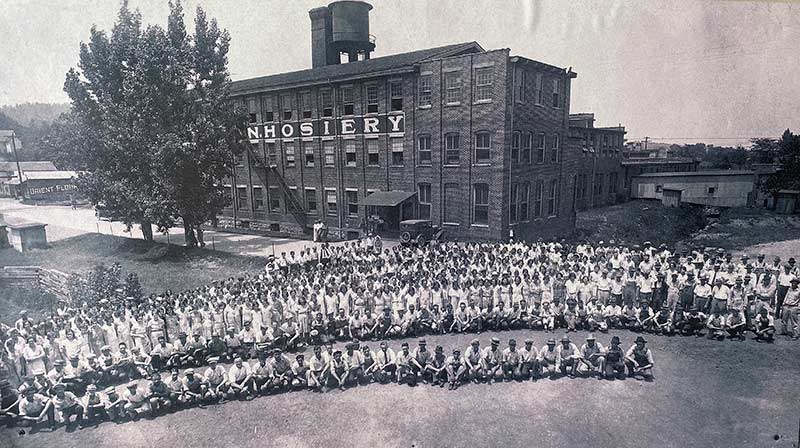

The industry for which Fort Payne became best known first came in 1907. It was that year, October 16 at 6:30 a.m. that the doors to the Florence Knitting Company opened for business. It housed 30 machines that knitted the socks. The building they began operations in once housed a Hardware Manufacturing Company in the late 1800’s during the discovery days of coal and iron ore in the hills and ridges of DeKalb County. It would later, and to this day, become known as the W.B. Davis Hosiery Mill, when March 15, 1915, Davis decided to increased his 10% share and be the major company stockholder.

The W.B. Davis and Son Hosiery Mill could probably be deemed the single most important manufacturing plant impacting the post 1890 boom economy of Fort Payne. It was the progenitor of an industry, which now makes Fort Payne the largest single location of hosiery manufacturing in America, and thus the title of “Sock Capital of the World”.

The mill was the largest industry in DeKalb County for many years, its payroll providing the principal cash flow for the area. Since boom days, DeKalb County had been dependent on agriculture, with cotton as the mainstay.

Davis acquired the old industrial building in 1915. Built in 1889 by the Alabama Builders’ Hardware Manufacturing Company it was intended to produce an extensive line of all grades of builders’ hardware. But the business failed to materialize before the boom era ended.

W.B. Davis was half owner of the United Hosiery Mills in Chattanooga during the first decade of the century. That mill was referred to as “Buster Brown Mill No. One,” after the trade name of its products. The Fort Payne mill began operation in 1913 under the name Buster Brown Mill No. Two, with Davis’ brother-in-law, James H. Witherspoon in charge. Davis later traded his stock in the Chattanooga mill for complete ownership of the one in Fort Payne. Coming to this city on January 1, 1915, he changed the name of the mill to the Davis name and began operating it with his son Robert E. Davis.

During World War II, the Davis mill played an important role in supplying socks for the military. Robert E. Davis perfected the cushion sole sock, and during the war produced and delivered over eight million pairs to the army alone.

During the peak of operation, W.B. Davis employed approximately 1,100 people. They were paid from $.10 to $.17 per hour in the early days. Although a dime an hour seems extremely low at this time, there were no other industrial jobs in Fort Payne and men working on farms were paid as little as 50 cents a day. Money was so scarce that employment at the mill was often considered a great opportunity.

Today the hosiery industry has countless machines operating in over 100 plants around the county.

Landmarks of DeKalb County

Landmarks of DeKalb County, Inc was organized as non-profit corporation on August 4, 1969, for the purpose of increasing and sharing knowledge of historical information and to encourage preservation of structures of historical significance in the DeKalb County area. From the organization’s first achievement, the purchase and restoration of the historic Opera House in downtown Fort Payne, to the present, Landmarks has served as a major instrument in preserving the history of DeKalb County’s people and places.